Associative algebra

In mathematics, an associative algebra A is an associative ring that has a compatible structure of a vector space over a certain field K or, more generally, of a module over a commutative ring R. Thus A is endowed with binary operations of addition and multiplication satisfying a number of axioms, including associativity of multiplication and distributivity, as well as compatible multiplication by the elements of the field K or the ring R.

In some areas of mathematics, associative algebras are typically assumed to have a multiplicative unit, denoted 1. To make this extra assumption clear, these associative algebras are called unital algebras.

Contents |

Formal definition

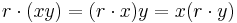

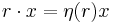

Let R be a fixed commutative ring. An associative R-algebra is an additive abelian group A which has the structure of both a ring and an R-module in such a way that ring multiplication is R-bilinear:

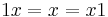

for all r ∈ R and x, y ∈ A. We say A is unital if it contains an element 1 such that

for all x ∈ A.

If A itself is commutative (as a ring) then it is called a commutative R-algebra.

From R-modules

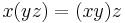

Starting with an R-module A, we get an associative R-algebra by equipping A with an R-bilinear mapping A × A → A such that

for all x, y, and z in A. This R-bilinear mapping then gives A the structure of a ring and an associative R-algebra. Every associative R-algebra arises this way.

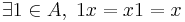

Moreover, the algebra A built this way will be unital if and only if

This definition is equivalent to the statement that a unital associative R-algebra is a monoid in R-Mod (the monoidal category of R-modules).

From rings

Starting with a ring A, we get a unital associative R-algebra by providing a ring homomorphism  whose image lies in the center of A. The algebra A can then be thought of as an R-module by defining

whose image lies in the center of A. The algebra A can then be thought of as an R-module by defining

for all r ∈ R and x ∈ A.

If A is commutative then the center of A is equal to A, so that a commutative R-algebra can be defined simply as a homomorphism  of commutative rings.

of commutative rings.

Algebra homomorphisms

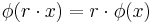

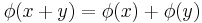

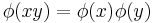

A homomorphism between two associative R-algebras is an R-linear ring homomorphism. Explicitly,  is an associative algebra homomorphism if

is an associative algebra homomorphism if

For a homomorphism of unital associative R-algebras, we also demand that

The class of all unital associative R-algebras together with algebra homomorphisms between them form a category, sometimes denoted R-Alg.

The subcategory of commutative R-algebras can be characterized as the coslice category R/CRing where CRing is the category of commutative rings.

Examples

- The square n-by-n matrices with entries from the field K form a unitary associative algebra over K.

- The complex numbers form a 2-dimensional unitary associative algebra over the real numbers.

- The quaternions form a 4-dimensional unitary associative algebra over the reals (but not an algebra over the complex numbers, since if complex numbers are treated as a subset of the quaternions, complex numbers and quaternions do not commute).

- The 2 × 2 real matrices form an associative algebra useful in plane mapping.

- The polynomials with real coefficients form a unitary associative algebra over the reals.

- Given any Banach space X, the continuous linear operators A : X → X form a unitary associative algebra (using composition of operators as multiplication); this is a Banach algebra.

- Given any topological space X, the continuous real- or complex-valued functions on X form a real or complex unitary associative algebra; here the functions are added and multiplied pointwise.

- An example of a non-unitary associative algebra is given by the set of all functions f: R → R whose limit as x nears infinity is zero.

- The Clifford algebras, which are useful in geometry and physics.

- Incidence algebras of locally finite partially ordered sets are unitary associative algebras considered in combinatorics.

- Any ring A can be considered as a Z-algebra in a unique way. The unique ring homomorphism from Z to A is determined by the fact that it must send 1 to the identity in A. Therefore rings and Z-algebras are equivalent concepts, in the same way that abelian groups and Z-modules are equivalent.

- Any ring of characteristic n is a (Z/nZ)-algebra in the same way.

- Any ring A is an algebra over its center Z(A), or over any subring of its center.

- Any commutative ring R is an algebra over itself, or any subring of R.

- Given an R-module M, the endomorphism ring of M, denoted EndR(M) is an R-algebra by defining (r·φ)(x) = r·φ(x).

- Any ring of matrices with coefficients in a commutative ring R forms an R-algebra under matrix addition and multiplication. This coincides with the previous example when M is a finitely-generated, free R-module.

- Every polynomial ring R[x1, ..., xn] is a commutative R-algebra. In fact, this is the free commutative R-algebra on the set {x1, ..., xn}.

- The free R-algebra on a set E is an algebra of polynomials with coefficients in R and noncommuting indeterminates taken from the set E.

- The tensor algebra of an R-module is naturally an R-algebra. The same is true for quotients such as the exterior and symmetric algebras. Categorically speaking, the functor which maps an R-module to its tensor algebra is left adjoint to the functor which sends an R-algebra to its underlying R-module (forgetting the ring structure).

- Given a commutative ring R and any ring A the tensor product R⊗ZA can be given the structure of an R-algebra by defining r·(s⊗a) = (rs⊗a). The functor which sends A to R⊗ZA is left adjoint to the functor which sends an R-algebra to its underlying ring (forgetting the module structure).

Constructions

- Subalgebras

- A subalgebra of an R-algebra A is a subset of A which is both a subring and a submodule of A. That is, it must be closed under addition, ring multiplication, scalar multiplication, and it must contain the identity element of A.

- Quotient algebras

- Let A be an R-algebra. Any ring-theoretic ideal I in A is automatically an R-module since r·x = (r1A)x. This gives the quotient ring A/I the structure of an R-module and, in fact, an R-algebra. It follows that any ring homomorphic image of A is also an R-algebra.

- Direct products

- The direct product of a family of R-algebras is the ring-theoretic direct product. This becomes an R-algebra with the obvious scalar multiplication.

- Free products

- One can form a free product of R-algebras in a manner similar to the free product of groups. The free product is the coproduct in the category of R-algebras.

- Tensor products

- The tensor product of two R-algebras is also an R-algebra in a natural way. See tensor product of algebras for more details.

Associativity and the multiplication mapping

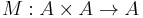

Associativity was defined above quantifying over all elements of A. It is possible to define associativity in a way that does not explicitly refer to elements. An algebra is defined as a map M (multiplication) on a vector space A:

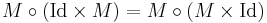

An associative algebra is an algebra where the map M has the property

Here, the symbol  refers to function composition, and Id : A → A is the identity map on A.

refers to function composition, and Id : A → A is the identity map on A.

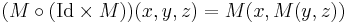

To see the equivalence of the definitions, we need only understand that each side of the above equation is a function that takes three arguments. For example, the left-hand side acts as

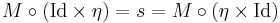

Similarly, a unital associative algebra can be defined in terms of a unit map

which has the property

Here, the unit map η takes an element k in K to the element k1 in A, where 1 is the unit element of A. The map s is just plain-old scalar multiplication:  ; thus, the above identity is sometimes written with Id standing in the place of s, with scalar multiplication being implicitly understood.

; thus, the above identity is sometimes written with Id standing in the place of s, with scalar multiplication being implicitly understood.

Coalgebras

An associative unitary algebra over K is based on a morphism A×A→A having 2 inputs (multiplicator and multiplicand) and one output (product), as well as a morphism K→A identifying the scalar multiples of the multiplicative identity. These two morphisms can be dualized using categorial duality by reversing all arrows in the commutative diagrams which describe the algebra axioms; this defines the structure of a coalgebra.

There is also an abstract notion of F-coalgebra.

Representations

A representation of an algebra is a linear map ρ: A → gl(V) from A to the general linear algebra of some vector space (or module) V that preserves the multiplicative operation: that is, ρ(xy)=ρ(x)ρ(y).

Note, however, that there is no natural way of defining a tensor product of representations of associative algebras, without somehow imposing additional conditions. Here, by tensor product of representations, the usual meaning is intended: the result should be a linear representation on the product vector space. Imposing such additional structure typically leads to the idea of a Hopf algebra or a Lie algebra, as demonstrated below.

Motivation for a Hopf algebra

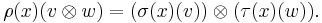

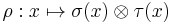

Consider, for example, two representations  and

and  . One might try to form a tensor product representation

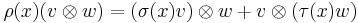

. One might try to form a tensor product representation  according to how it acts on the product vector space, so that

according to how it acts on the product vector space, so that

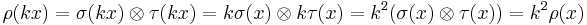

However, such a map would not be linear, since one would have

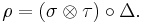

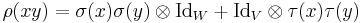

for k ∈ K. One can rescue this attempt and restore linearity by imposing additional structure, by defining a map Δ: A → A × A, and defining the tensor product representation as

Here, Δ is a comultiplication. The resulting structure is called a bialgebra. To be consistent with the definitions of the associative algebra, the coalgebra must be co-associative, and, if the algebra is unital, then the co-algebra must be unital as well. Note that bialgebras leave multiplication and co-multiplication unrelated; thus it is common to relate the two (by defining an antipode), thus creating a Hopf algebra.

Motivation for a Lie algebra

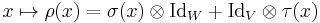

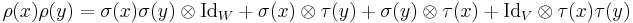

One can try to be more clever in defining a tensor product. Consider, for example,

so that the action on the tensor product space is given by

.

.

This map is clearly linear in x, and so it does not have the problem of the earlier definition. However, it fails to preserve multiplication:

.

.

But, in general, this does not equal

.

.

Equality would hold if the product xy were antisymmetric (if the product were the Lie bracket, that is, ![xy \equiv M(x,y) = [x,y]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7a13d117218e9fcf082fee25ecc88b0a.png) ), thus turning the associative algebra into a Lie algebra.

), thus turning the associative algebra into a Lie algebra.

References

- Bourbaki, N. (1989). Algebra I. Springer. ISBN 3-540-64243-9.

- Ross Street, Quantum Groups: an entrée to modern algebra (1998). (Provides a good overview of index-free notation)